On the Figuration of the Civic Poet as Hlayq·a (a text by Joachim Ben Yakoub on ‘An Audio Family Album’)

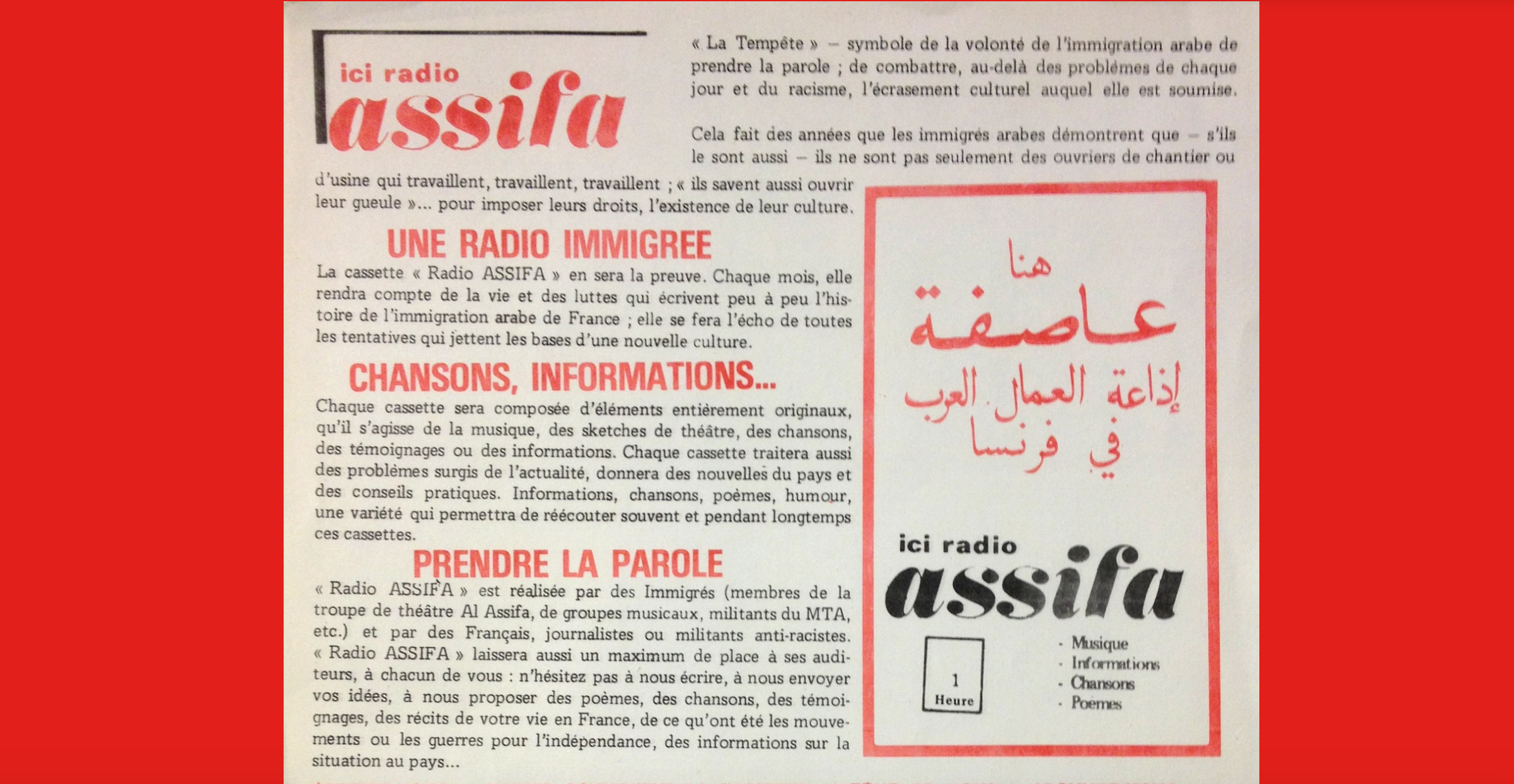

Bouchra Khalili’s proposition for The Diasporic Schools at the Kunstenfestivaldesarts 2020 begins with a series of individual encounters with members of a new generation of Maghrebi artists and activists in Brussels, later to be complemented with moments of contact in other European cities. Out of the relations shaping these meetings and conversations, she is forming a living online family album of voices, re-establishing stories of resistance and repairing memories of rebellion. In her search for the meaning of voices produced by the persistence of history resonating and echoing in the present, to paraphrase Khalili, she decided to close her eyes and listen to the murmurs circulating and resonating in the diasporic al-halqa of Brussels. To convey these family stories to her audience, Khalili returns to the collaborative methods of her previous work, reconsidering the figuration of the civic poet as hlayqi·a. The title of her 2017 video installation, The Tempest Society, is not a reference to Shakespeare’s last seminal play or to Aimé Césaire’s critical adaptation, but rather to the legacy of Al Assifa, a self-organised autonomous theatre company created in 1973 by Maghrebi workers, partisans of the Arab Workers’ Movement in Paris. Both the journal of the movement and the theatre company were named after the armed revolutionary wing of Fatah, Yasser Arafat’s Palestinian National Liberation Movement, highlighting the workers’ allegiance to their origins in the French Palestine Committees since 1967. The group engaged in new forms of improvised action theatre and agitprop, playing during factory strikes and in community spaces and occupied public squares. Simultaneously, they were active in a variety of demonstrations against rampant racism and police violence, and in defence of dignified working conditions, continuously acting in a spirit of internationalist solidarity. In the constructed narrative of The Tempest Society, stories of anti-colonial struggle and internationalism intertwine with tales of civic becoming.

For An Audio Family Album Khalili re-established a precise link, not so much with the heritage of Al Assifa at large, but with the various ways in which Al Assifa created the conditions for stories and information to circulate in the diaspora. In response to low literacy levels among Arab workers in Paris at the time, some of the members of Al Assifa chose to read aloud the most important news items from the daily newspaper in cafés where workers congregated. The group also set up Radio Assifa and distributed cassette recordings of their chronicles to keep the community up to date on the state of affairs of different social and political conflicts and mobilisations. Most importantly, Al Assifa revived the endangered form of al-halqa, once a widespread and subversive performing art in the Maghreb, in order to reflect on the ambiguity of the power relations shaping current events around them, in particular the racist murder of the young Djellali Ben Ali or the murder of Mohamed Diab at the hands of the police. In al-halqa – to paraphrase Phillipe Tancelin, one of Al Assifa’s founder members – the storyteller does not have the authority of the author; as the conveyor of a collective and historical discourse, he or she is subjected to real and equal questioning by the public and can thus be challenged by the audience at any moment during any public performance.

The re-emergence of al-halqa as a circular performative form in the diasporic context of the Arab workers’ movements in Paris in the 1970s is intricately linked to the various ways in which the anti-colonial struggle seeped through the Maghrebi theatre landscape, in which discussions arose about different strategies to decolonise the dramatic repertoire and its canon. The return of both the device of the storyteller (hlayqi/hlayqia) and the circular arrangement of the performance made space for hybrid theatrical forms traversed by fantastic, mythical and historical tales, with characters and figures anchored in the translocal histories of the Maghreb, and theatrical modalities borrowed from Amazigh and Islamic traditions, as well as Brechtian aesthetics and documentary theatre. This hybridisation strongly influenced the work of a new movement of theatre makers, represented by figures such as Kateb Yacine, Abdelkader Alloula and Tayeb Saddiki, each of whom, in their own way, combined different performative approaches with popular forms, wielding experimental and politically engaged poetics with a certain sense of ceremoniality. The circulation of vital energy inside al-halqa rendered theatre a sensitive experience again, repairing life and its reverse in its most vulnerable form in the fleeting process of world-making. Theatre regained its function as a distant, interactive but always critical mirror, questioning and subverting what can be said or heard and what should remain silenced, reconsidering what is visible and what is indiscernible, and reinstating the oral narrative as a powerful from of resistance to hegemonic discourse and ways of knowing and sensing the world.

In An Audio Family Album, Bouchra Khalili relates to the endangered circular form of al-halqa central to Al Assifa’s practice to rearticulate the uncanny intricacies of diasporic family stories. In doing so, she taps into the contemporary need to tell forgotten stories of resistance and liberation, but also to generate new oral forms, and through these forms reinvent new tales and myths. Together they have the potential to constitute what Stuart Hall calls a living archive or, in this case, a living family album. Through their performed orality, the family stories told in al-halqa remain in a permanent state of suspension. Like diaspora itself, the animated form of al-halqa is inherently unstable, nomadic and always moving in different directions, so the family stories told and the relations formed never fully crystallise, surpassing the scriptocentric limits of the written world. By doing so Khalili holds space for the possible resurgence or re-emergence of silenced and erased memories, to re-world the divided world we inhabit today.

In The Tempest Society Khalili invited three different Athenian students to summon the presence of the Al Assifa group through their own first-hand diasporic experiences of racism and xenophobia, alternated with readings of Al Assifa’s manifesto Les Tiers-Idées (1997) and selected excerpts of the novel My Name is Europe by Gazmend Kapllani. In her proposal for The Diasporic Schools, however, Khalili invites a new generation of Maghrebi artists and activists to read exhumed family stories of liberation that have influenced their past and retain the potential to inspire current forms of diasporic resistance, all the while becoming part of a newly constituted family album. Inspired by the legacy of Pier Paolo Pasolini, Khalili calls on these artists and activists to embody the figuration of the civil poet as hlayqi·a, oscillating through free indirect speech in an intertextual play between historical citations and personal narratives, speaking through concerned and involved individuals to re-assemble and render audible a conversant collective voice. Not giving voice to, but speaking nearby those who are absent or silenced in order to bear witness to the various ways historical injustices can be continuously resisted. Going beyond the representational restriction of time and space in the fabulation of a family album, a people to come is invented that prefigures a world to come, where the diasporic would a priori be inscribed in every school, remembering the ancestral lineage of resistance that made a free and dignified life possible.