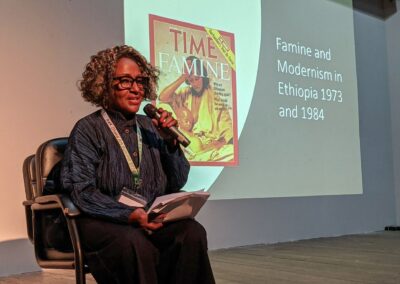

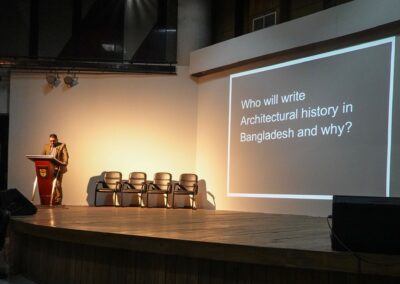

The Dhaka Art Summit, Institute for Comparative Modernities (ICM) at Cornell University , and Asia Art Archive, with support from the Getty Foundation’s Connecting Art Histories initiative, launched a new research project entitled Connecting Modern Art Histories in and across Africa, South and Southeast Asia. The project brought together a team of leading international faculty and emerging scholars to investigate parallel and intersecting developments in the cultural histories of modern South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Africa.

Shaped by shared institutional and intellectual developments that are closely related, these regions are marked by similar experiences during the twentieth century. These include the rise of modern art practices associated with the withdrawal of colonialism and the consolidation of nationalism, the founding of institutions such as the art school and the museum, and increasing exchange with international metropolitan centers via travel and the movement of ideas through publications and exhibitions. Viewing this in terms of statist and national art histories obscures their analysis in a comparative framework. By contrast, this program emphasizes a connected and contextualized approach to better understand both common developments as well as divergent trajectories.

MAHASSA is a collaborative research project whose partners include the Dhaka Art Summit, Asia Art Archive (Hong Kong), and Institute for Comparative Modernities at Cornell University (USA). The project brings together a team of leading international faculty and emerging scholars to investigate parallel and intersecting developments in the cultural histories of modern South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Africa. Comparative study of the development of practices, pedagogy, institutions, and circulation can be very insightful in critically situating local and national developments, as well as in recognising transnational dimensions to the rise of modern art and its institutions in this vast region. The first set of meetings was held in Hong Kong during August 2019; Dhaka Art Summit hosted the second convening of MAHASSA which included focused seminars, panel discussions, public talks, and presentations by participants. Details of the participants are given here: https://www.dhakaartsummit.org/connectingarthistoriesLINKS

FILES

AUDIO